I

Mea Shearim

During the 1870s, the city within the walls of Jerusalem was undergoing a severe crisis. An increase in population, especially in the Jewish quarter, resulted in high housing prices and poor sanitation. The Ottoman government failed to remove garbage dumps. Eventually, the pollution seeped into the water pits, causing a rise in disease and mortality rates among the population within the walls. These problems drove the Jewish community to establish neighborhoods outside the walls, and by 1873, four such neighborhoods were built - "Mishkenot Sha'ananim" (1880), "Mahane Israel" (1886), "Nahalat Shiva" (1869) and "Beit David" (1873).

A small group of about one hundred young Ashkenazi Jews believed that moving outside the walls would help them improve their standard of living. In 1874, they decided to combine their resources. They were able to purchase a tract of land outside the walls for a new settlement. It would contain one hundred houses that will operate as the fifth neighborhood outside the city walls. The name they chose for that piece of land, Mea Shearim, was derived from a verse in the Torah portion that was read in the week the neighborhood was founded: "Isaac sowed in that land, and in that year he reaped a hundredfold (מאה שערים, Mea Shearim); God had blessed him" (Genesis 26:12).

Construction began around April 1874 by both Jewish and non-Jewish workers. Contractors, builders, and plasterers were Christian Arabs from Bethlehem, and Jewish craftsmen also contributed. By December 1874, the first ten houses were standing. At first, Mea Shearim was a courtyard neighborhood surrounded by four walls with gates that were locked every evening. By October 1880, 100 apartments were ready for occupancy, and a lottery was held to assign them to families. Between 1881 and 1917, even more houses and neighborhoods were built in Jerusalem. New neighborhoods surrounded Mea Shearim and helped establish a significant Jewish presence outside the walls. By the turn of the century, there were 300 houses, a flour mill, and a bakery. Mandatory Palestine under the British administration had been carved out of Ottoman southern Syria after World War I. The British civil administration in Palestine operated from 1920 until 1948. During its existence, the country was known simply as Palestine. The residents of Mea Shearim welcomed the British regime, which maintained good relations with the authorities for the neighborhood's good. As a result, access roads to the area were improved, the neighborhood markets prospered, old shops were renovated, and new shops opened. Mea Shearim continued to grow; by 1931, it was the third-largest neighborhood in Jerusalem. This growth enhanced the neighborhood's status and importance. Still, daily life became more complex, as many houses were populated with numerous people, resulting in sanitary conditions that endangered their health. A rise in poverty resulted in a deterioration of the house's outer appearance and a spread of diseases. The neglect of the Ottoman regime continued to set the tone, and the lack of proper drainage caused rain to flood the streets and even people's homes.

The neighborhood's uniform appearance also began to change as different construction materials came into use, resulting in non-uniform façades, and cheap tin became an alternative to the Jerusalem stone commonly used for construction. In 1948 the Arab–Israeli war broke out, and Jerusalem as a city was divided between Israel and Jordan. The border was close to Mea Shearim, and the neighborhood suffered military attacks and building damage. Within the next 20 years, the community would suffer from a decreasing population as the children of the second founding generation moved to orthodox neighborhoods nearby, leaving as few as 170 houses occupied out of a total of 304. In later years the residents returned, and the population grew once again. The population remained isolated and segregated because it refused to cooperate with the government of Israel. Street posters (Pashkvilim) began to appear on public walls calling on residents not to serve in the Israeli army, not to vote or be elected to the Israeli parliament, and not to participate in Israel's Independence Day celebrations.

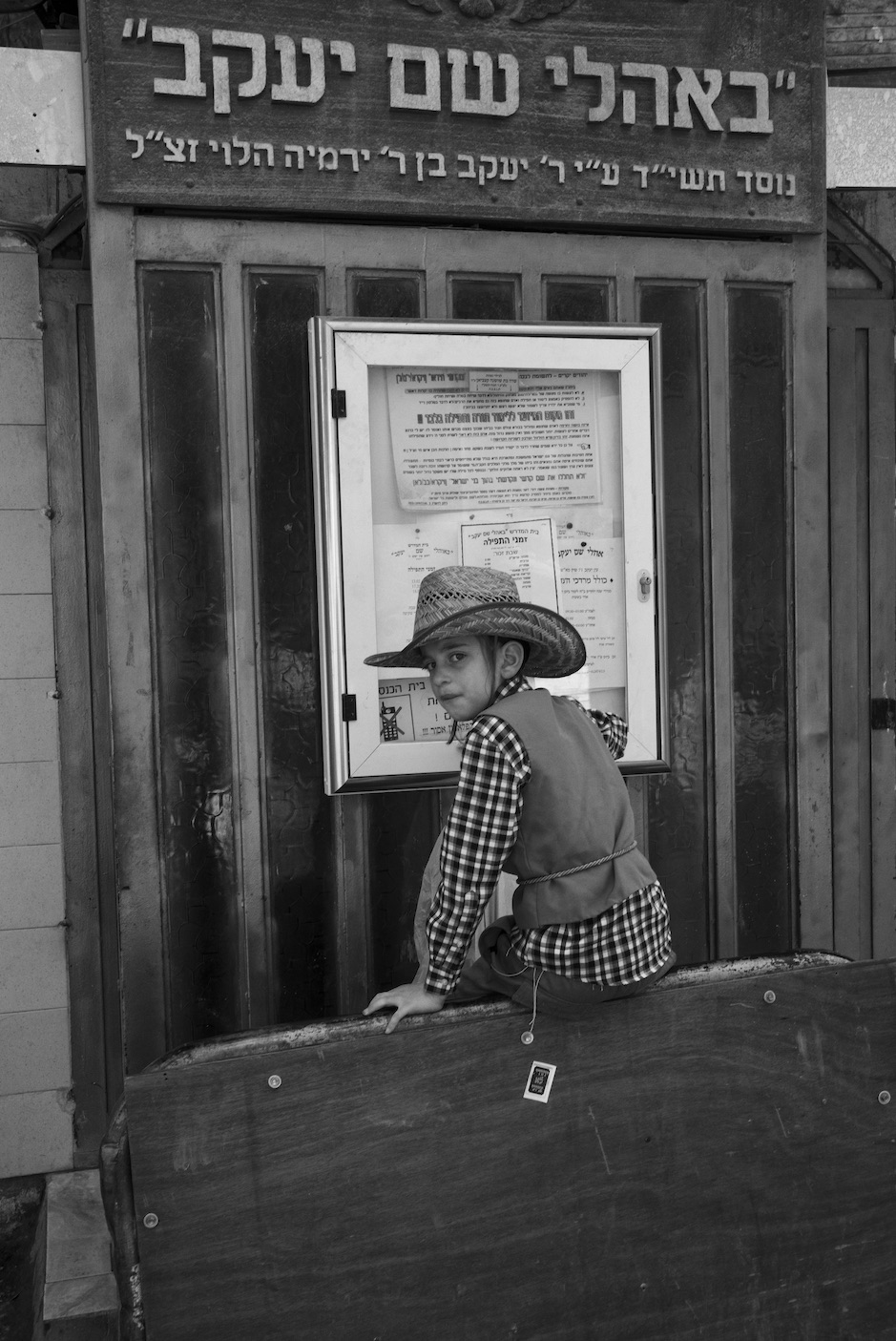

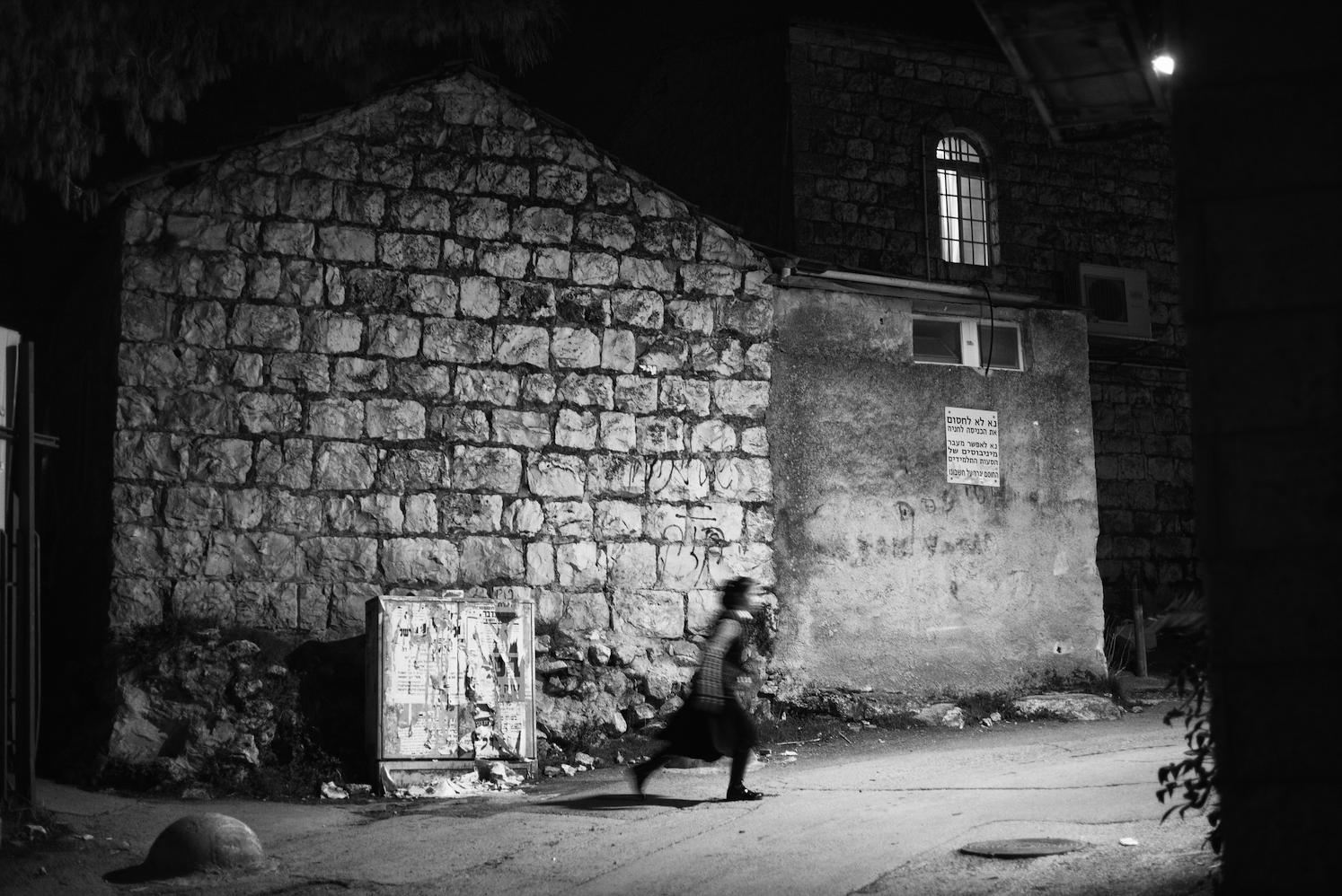

Today, Mea Shea rim remains loyal to its old customs and preserves its isolation in the heart of Jerusalem while trying to stave off the modern world; it is, in a way, frozen in time. The numerous renovations of houses at the end of the 20th century hardly affected the neighborhood's appearance. They are still common today but fewer in numbers. Homes built over one- hundred years ago stand alongside a few new ones.

The life of the Hasidic community still revolves around strict adherence to Jewish law, prayer, and the study of Jewish religious texts. Most of the people are Ashkenazim; there are hardly any Sephardic Jews in the neighborhood. In addition to some well-to-do families, there are also many needy ones, which local charity institutions help.

The traditional dress code remains in effect here; for men and boys, it includes black frock coats and hats. Long, black beards cover their faces; many grow side curls called "payouts." Women and girls are urged to wear a modest dress – knee-length or longer skirts, no plunging necklines or midriff tops, no sleeveless blouses or bare shoulders. Some women wear thick black stockings all year long, and married women wear various hair coverings, from hats to wigs and headscarves. The common language of daily communication in Mea Shearim is Yiddish, in contrast to Hebrew, spoken by most of Israel's Jewish population. Hebrew is used by the residents only for prayer and religious study, as they believe that Hebrew is a sacred language to be used only for religious purposes.

This is the ongoing battle between old and new—the past versus the present—the everyday life of a city within a city.

My grandmother and I had a special bond. We developed a habit that once a week, usually on Mondays, we cleared our schedule and sat down to discuss the photographs I took. We shared ideas about the stories, the people, and even how the weather affected the light in the pictures. At first, photography was something foreign for both of us, and with time, we developed a passion for it. We loved our gatherings and anticipated them every week. In early 2014, things changed. We had fewer opportunities for our weekly routine as her health had begun to deteriorate. She received treatments weekly and eventually had to be under medical supervision and hospitalized. On one of the visits, as I sat by her bed, I wanted to ease her mind from the treatments she received and asked if she would like to see a photograph I had taken the day before. She immediately said yes and was enthused when I showed her the picture. We ended up taking and analyzing the photo as we used to, freeing our minds from the hospital room we were in. Neither of us knew that it would be our last time together. After her death, I decided to do a project based on the last photograph she ever saw. This one photo has led me on a journey, photographing the streets of Mea Shearim.